Lotus Sutra—the Light of Humanism and Peace

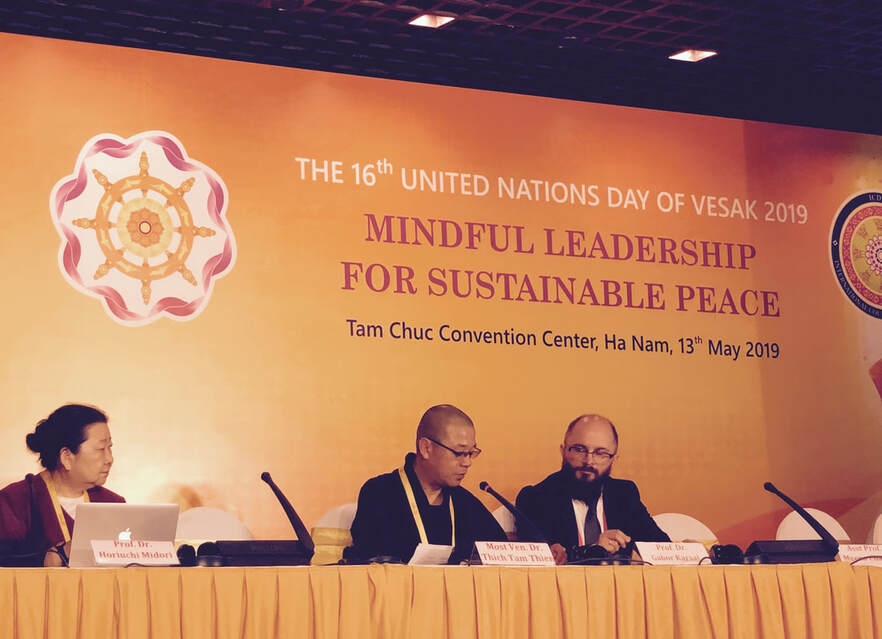

Most Ven. Dr. Khai Thien a.k.a Thich Tam Thien

(Celebration of the United Nations Day of Vesak BC 2564–2019)

On the occasion of the celebration of the United Nations Day of Vesak 2019 in Vietnam, and in commemoration of the great and noble Dharma teachings of the Shakyamuni Buddha, I would like to offer some reflections on the Lotus Sutra—one of the last Dharma lectures given by the Buddha at the holy mountain of the Vulture Peak (Gṛdhrakūṭa), also known as the Holy Eagle Peak, in what is now Bihar, India.

The Lotus Sutra (saddharma puṇḍarīka sūtra) is one of the most popular sutras in the Mahāyāna Buddhist tradition, which is also sometimes referred to as “Developed Buddhism.” According to Mahāyāna scholars, the philosophy of the Lotus Sutra is very important, and can guide us in dealing with modern-day problems. All the causal origins of human suffering—from inner anguish to poverty, sickness, and all kinds of wars and conflicts within each person, family, community, nation, and even worldwide—were illuminated through the Buddha’s wisdom (Tathāgata-jñāna) in the Lotus Sutra. The sutra’s resolutions are generous and thoughtful, and pertain not only to the issue of division and conflict among divergent Buddhist schools in ancient times—around the first century AD when the Lotus Sutra was disseminated—but also to the problems of today. In fact, in our day, the wars are still there, discrimination is still there, inequality and bigotry are still there, social injustice and poverty are still there, and the dream of world peace is still earnestly expressed in our daily prayers. And the Lotus Sutra’s teachings are still there. They may serve as the spiritual light that will guide us, the sons and daughters of the Buddha, in securing peace and happiness.

I. The Philosophy of Humanism in the Lotus Flower

The first message of the Lotus Sutra comes from its title: “The Lotus Flower of the Wonderful Dharma, the Dharma for Bodhisattvas, the Dharma upheld by the Buddhas” (The Lotus Sutra, 2012), or in Chinese,“妙法蓮華教菩薩法佛所護念.”(Sanskrit: saddharma puṇḍarīka, bodhisattvāvavādam, sarva-buddha-parigraham; The Lotus Sutra,2015).

Wonderful Dharma (妙法, saddharma) is the highest truth, the absolute truth, the supreme noble Dharma, the true wisdom of the Buddha (Tathāgata-jñāna-darśna), which contained the Buddhahood, the essence of the pure mind. In Sanskrit, the term Tathāgata-jñānameans “the insight of Tathāgata,” which indicates not only the Shakyamuni Buddha’s wisdom but also the Buddhahood that is latent in all sentient beings. The Buddhahood inside each of us is the potential to become a Buddha, to reach full enlightenment. This ability is implicit within every individual, regardless of age, race, or gender. In the second chapter of the Sutra, we read:

“Śāriputra! What is the one great purpose for which the Buddhas, the World-Honored Ones, appear in the worlds? The Buddhas, the World-Honored Ones, appear in the worlds in order to cause all living beings to open (the gate to) the insight of the Buddha, and to cause them to purify themselves. They appear in the worlds in order to show the insight of the Buddha to all living beings. They appear in the worlds in order to cause all living beings to obtain the insight of the Buddha. They appear in the worlds in order to cause all living beings to enter the Way to the insight of the Buddha. Śāriputra! This the one great purpose for which the Buddhas appear in the worlds.” (The Lotus Sutra, 2012)

All sentient beings have the ability to reach the state of full enlightenment and become a Buddha by nature. For this reason, the Buddhas come into the worlds with the one great purpose to open, to show, to cause sentient beings to obtain and enter into the Way to the insight of Tathāgata (samādāpana/samdarśana/pratibodhana/avatārana) (The Lotus Sutra, 2015).

In reality, everyone carries a different karmic condition—different kinds of happiness and sufferings, different kinds poverty and riches. The same can be said of nations and the global community. Certainly, the life of each living being and every nation depends on the karmic forces of both the individual and the collective. For human beings, our impure karma is like a muddy puddle. But it is this very muddy puddle from which a beautiful lotus flower can germinate, grow, and blossom into the air. Indeed, mud, water, and air are the three necessary conditions for a lotus flower to bloom. In the symbol of the lotus flower, given in the title of the Lotus Sutra, Lord Shakyamuni Buddha has given us a great and unique path of spirituality.

However, being human, we are unable to reject our own karmic force, to be free from sufferings and to live in happiness, even temporarily. In the same way, the wars and conflicts of our time cannot be resolved by sheer will; they are in bondage to the collective karmic force. Only through the personal practice of mental purification can karma be transformed, as when leaching water out of mud. Thus, the Buddha taught that we are unable to run away from our sufferings; we must transform them and generate our own source of happiness by meditating deeply on the true causes of sufferings. Put another way, in order for our dream of peace and happiness to become true, we must reflect on the true nature of life. The Buddha spoke of that true nature of life in the teaching of the Ten Suchnesses—that is, the factors common to all things: their appearances as such, their natures as such, their entities as such, their power as such, their activities as such, their primary causes as such, their environmental causes as such, their effects as such, their rewards and retributions as such, and their equality as such (The Lotus Sutra, 2012, chapter 2). The Ten Suchnesses govern the operations of both sentient and non-sentient beings, humans and the cosmos, completely recognized by the wisdom of the Buddha.

In the Lotus Sutra, the parable of the poor son (daridra-puruṣasya) (The Lotus Sutra, 2012, p.90) reminds us that no matter how poor and miserable a man is, he still possesses a priceless heritage—that is, the Buddhahood (buddhatva)inherent in each person. Thank to this intrinsic Buddhahood, a person has the ability to become a Buddha, to overcome all troubles and adversities, and go beyond the three worlds of afflictions (trailokya).[1]Therefore, if the wonderful Dharma (妙法, saddharma) or the insight of the Buddha (知見仏,tathāgata-jñāna-darśna) did not exist perpetually within each person or each sentient being, where could a person’s spiritual journey lead? Also, if the final destination of a spiritual journey of a religious practice is merely to be reborn in a higher realm of happiness, that journey is somewhat meaningless. In the Lotus Sutra, Lord Buddha taught that the aim of spiritual practice is to obtain the insight of Buddha (Tathāgata-jñāna-darśna), to become a Buddha, or to be fully enlightened, and that only the insight of Tathāgata—the ultimate state of full enlightenment—brings a spiritual journal to its complete and perfect end. From these noble teachings, a new dimension of the spiritual journey, a true path of enlightenment and liberation, which is by nature creative, proactive, and independent, has been opened to all sentient beings, especially to human beings. On this path, everyone—no matter who they are—can practice Dharma with the multiple means available in the teachings of the three vehicles (tri-yāna: śrāvaka, pratyekabuddha, andbodhisattvā).

In the light of universal Buddhahood, we are able, despite our many differences in culture, geography, and race, to join together in harmony and overcome all diversities. Clearly, in such a divine teaching, differences in skin color or race have no meaning at all. Here, the light of wisdom of the wonderful Dharma is indeed shining brightly. That light is one of humanistic philosophy. Perhaps it is hard for us to find such a Dharma in any system of philosophy, whether ancient or present.

There is a story in the Lotus Sutra, in the chapter “Devadatta,” about the Dragon-king Sāgara’s daughter (sāgaranāgarāja-duhitā), who became a Buddha when she was just eight years old (The Lotus Sutra, 2012). The story is striking because it conveys the true universality of Buddhism, namely, that even an animal—one that is still so young, and a female—shows the potential to become a Buddha and that this potential is present in equal measure in all living beings regardless of age, gender, or race. This story appeared more than two thousand years ago in India, in the context of great discrimination against social classes, women, and children. It is indeed a great progressive and liberal doctrine.

Even in our modern societies, war and conflict often originate in disagreements over or misunderstandings about beliefs and religious philosophies. In such circumstances, we are able to recognize the nobility and compassion in the teachings of the Buddha in the Lotus Flower of the Wonderful Dharma. Its message that all sentient beings have the seed of Buddha within is the true insight of Tathāgata; it is the divine wisdom that is able to liberate human beings from the bondage of blind belief such as being a slave to an unknown spirit. From this point of view, our lives become more harmonious and transcends all barriers established by prejudice.

II. The Way of Securing Peace and Happiness

Following the phrase “Lotus Flower of the Wonderful Dharma” is the phrase “Dharma for Bodhisattvas” (教菩薩法, bodhisattvāvavādam), literally translated as “the Teachings for Bodhisattvas.” Some people may think that these teaching are only for Bodhisattvas, and they exclude themselves from concerning about the teachings. But this is not so. When Lord Shakyamuni Buddha delivered the Lotus Sutra, the audience included all kinds of sentient beings. As recorded in the first chapter of the sutra, there were Arhats, Bodhisattvas, Śakra-Devānām-Indra, Dragon-Kings, Asura-King, Garuda-King, King Ajātaśatru, bhiksus, bhiksunis, upasakas, upasikas, gods, dragons, yakasa, gandharvas, asuras, garudas, kinnaras, mahoragas, humans and non-humans, accompanied by hundreds of thousands of their attendants. The Buddha often emphasized that he had, by many means (upāya), expounded to sentient beings the Dharmas of three vehicles (śrāvaka,pratyekabuddha, andbodhisattvā) with which audiences of different levels may follow in the Buddha’s way. But only the Buddha-vehicle (buddhayāna) is the uppermost Dharma.

In order to enter the Buddha-vehicle, devoted Buddhists must study and practice the way of the Bodhisattvā. A Bodhisattva is a person who vows to put all personal efforts into caring for other’s sufferings and hardships. A Bodhisattva practices his or her own aspirations without any concept of self or ego. Therefore, the true life-mission of a Bodhisattva is to rescue sentient beings and to teach the Dharmas to all. In the Lotus Sutra, the Buddha stressed the spirit of saving others. He himself had given a prophecy of enlightenment—not only for his present audience but for all the audiences of the future, after the Buddha had reached nirvana. Those who reflect on the Lotus Sutra with joy for even a moment, believing in the ability of all to become Buddha, will eventually attain enlightenment. Consequently, the Bodhisattva’s aspiration, according to the Lotus Sutra, is that no sentient being should be excluded from achieving enlightenment, no matter who they are, no matter what they are guilty of.

The image of the Bodhisattva Sadāparibhūta (The Lotus Sutra, 2012, chapter 20) who bowed to anyone he met and praised each person’s potential to become a Buddha, is an excellent example of the Bodhisattva’s way. Bodhisattvas are ready to sacrifice their lives to help cultivate the Buddhahood implicit in every being. Sharing the light of spiritual enlightenment with others is truly necessary, as once a person attains personal enlightenment, its value will stay with him/her forever. That kind of work is not easy, but is the very noble path of spiritual practice. Helping others cultivates merit, benefiting both self and the other.

Moreover, the Buddha taught that not only is the human world constantly unsafe, but also that the three realms of karma, form, and formlessness are like a burning house (The Lotus Sutra, 2012, p.52). Transcendence beyond the burning house of the three worlds is the true destination of Buddhist practitioners. From this point of view, in order to have a true life of peace and happiness, one should think of not only the sufferings of those around them but also those of the whole world, because in that world, we have relatives—both secular and spiritual. Suppose that a person is lucky enough to have happiness and peace; however, how can we live happily and peacefully while the world around us is full of anguish, hostility, distress, conflict, and fighting? We must help those who are sunken in the realm of afflictions and misery to recover their own peace, particularly inner peace. This is the thoughtful mentoring work of a Bodhisattva. This is also the basic work of a Buddhist, especially one in a place of leadership in a family, community, society, or nation.

There is a famous Zen saying in Buddhism: “Peace in the mind, peace in the world.” When the individual mind is at ease, the world can have peace. Individual happiness has a great effect on family and society, but the suffering of each individual has the same effect, no more no less. Thus, dwelling in the realm of quietness and maintaining a sense of personal satisfaction as illustrated in the nirvana of Śrāvaka (the Hearer) is not the ultimate destination of the Bodhisattva’s will. Hence, the Lotus Sutra praises and promotes teaching the Dharmas as a road of cultivating merit and virtue dedicated to all sentient beings, and thus together achieving the Buddhahood; that is thehighest and perfect awakening (anuttara-samyak-saṁbodhi). The Buddha Shakyamuni Tathāgata himself is, as we learn in the Lotus Sutra, still walking on the path of Dharma teaching. “The Life Span of the Tathāgata,” chapter 16, says that the Shakyamuni Tathāgata, from past uncountable kalpas (aeon) until now, is still on the path of Dharma teaching in the Sāha world (human world) as well as worlds outside this world, and that he will never enter nirvana. Thus, the Shakyamuni Tathāgata illuminates the true meaning of peace and the true path to peace.

III. Always Upheld by the Buddhas

The last phrase of the Lotus Sutra’s title is “Dharma upheld by the Buddhas” (佛所護念, sarva-buddha-parigraham). Literally, this means that the Buddhas always uphold and protect this Dharma. The Shakyamuni Tathāgata affirms that the Lotus Sutra is the hidden core of the transcendental powers of all the Buddhas,—the Tathāgatas of the past, present, and future—and that those who embrace, read, recite, expound upon, and copy the Lotus Sutra, even one verse or one phrase, or even for a moment think of it with joy, are upheld and protected by all the Buddhas of the past, present, and future. This gives us a clear message about the significance of the Lotus Sutra’s philosophy of saving sentient beings, who are all deemed to possess Buddhahood deep within. This is the very basis for sustaining world peace. If there is no commonality, persons from different backgrounds cannot join together in harmony. But we know that people always want to live in happiness and experience the ultimate truth of life, no matter where they live or who they are. The ultimate truth, as explained in the Lotus Sutra, is the very Lotus Flower of the Wonderful Dharma(saddharma puṇḍarīka).

In the limited frame of human history, the Shakyamuni Tathāgata, from birth to nirvana, taught the philosophy of saving sentient beings in various methods suitable for sentient beings of all levels and capacities. He taught this truth not only to human beings but also to celestial beings in the three realms. Although celestial beings live at a higher level of merit than human beings, the Buddha taught them to practice Dharma and guided them toward a still more perfect realm—that is the realm of complete enlightenment (anuttara-samyak-saṁbodhi). In the wisdom of the Buddha, both suffering and happiness arise from wholesome or unwholesome karmas. Thus, even the blissful life of celestial beings cannot last long. Nothing can secure life in the heavens if it is not illuminated and directed by the light of enlightenment (saṁbodhi).

For this reason, before entering nirvana, the Shakyamuni Tathāgata once again emphasized one Dharma, which is protected and upheld by all the Buddhas in the past, present, and future. This is the supreme Dharma: to help germinate the seed of Buddhahood in all sentient beings. One particularly lively image that illustrates the Buddha’s veneration of this one Dharma is recorded in chapter 11 of the Lotus Sutra, “The Emergence of the Treasure Tower”:

A Buddha named Many Treasures Tathāgata (Prabhūtaratna) had passed through many thousands of billions of kalpas. His body was placed in a stūpa (tower) and worshipped. When the Shakyamuni Tathāgata was delivering the Lotus Sutra in this world, his stūpa appeared so that he was able to directly listen to, prove, and praise the truth of the Lotus Sutra. For in the past, when the Many Treasures Tathāgata was yet practicing the way of Bodhisattva, he made a great vow: “If any one expounds the sutra called the Lotus Flower of the Wonderful Dharma in any of the worlds of ten quarters after I become a Buddha and pass away, I will cause my stūpa-mausoleum to spring up before him so that I may be able to prove the truthfulness of the sutra and say ‘excellent’ in praise of him, because I wish to hear that sutra.” (The Lotus Sutra, 2012, p.187)

Although this story has many levels of meaning, the essential point of it illumines the spirit of compassionate protection of all the Buddhas over all those who desire to receive the teaching of the one Buddha vehicle (buddhayāna). The protection of all the Buddhas, past, present, and future, is the original source of Buddhist spirituality, which is not confined to this life or the afterlife, but exists permanently, always and everywhere. It is like the moon in the sky, which presents itself constantly even if the moon in the lake appears and disappears.

The Shakyamuni Tathāgata, for all his life, expounded the one Buddha vehicle (ekayāna/buddhayāna) equally to all living beings. On the path of teaching such a Dharma, there is no discrimination between this person or that person; the difference is in the level of teaching only. The content of the Dharma is always the same. As Buddhahood has only one taste, so does the truth also have only one taste. If a Buddhist practitioner and a Hindu Brahmin walk on the same road, the road of buddhayāna, the destination for each is the same: Buddhahood. In this sense, the Wonderful Dharma (saddharma) is considered the universal truth of great wisdom. Thousands of years before or thousands of years after, this truth is the same. Thus, Buddhists around the world firmly believe that all the Buddhas of the three lives (past, present, and future) constantly and silently give protection and assistance to those who have devotionally borne the bodhi heart of enlightenment.

In brief, although we live more than 2600 years after the Buddha, the ancient Dharma lecture on the Lotus Sutra from Shakyamuni Tathāgataat the peak of the holy mountain Gṛdhrakūṭa is yet shining on us. Like the golden sun in the east, the spiritual power from the message “Lotus Flower of the Wonderful Dharma, the Dharma for Bodhisattvas, the Dharma upheld by the Buddhas” (saddharma puṇḍarīka, bodhisattvāvavādam, sarva-buddha-parigraham) still saves us and helps us transcend all barriers and overcome all afflictions. Indeed, the concept of peace would be empty if the Buddhahood were not there. Religion would also fade if there were no light of enlightenment. And human happiness will not last long if the bodhi heart is absent.

Namo Shakyamuni Tathāgata

References

The Lotus Sutra. (2012). Translated by Senchu Murano. Hayward. CA. NBIC.

The Lotus Sutra. (1993). Translated by Burton Watson. (1993). New York. Colombia University Press.

The Lotus Sutra. (2015) Translated and Edited by Ueki Masatoshi. 梵漢和対照. 現代語訳法華経(Lotus Sutra Sanskrit, Chinese, and Japanese comparison). Iwanami Shoten. Tokyo. p.38 /saddharmapuṇḍarīkam, dharma-paryāyam sutrantam mahā-vaipulyam bodhisattvāvavādam, sarva-buddha-parigraham.../

The Lotus Sutra. (2015) Translated and Edited by Ueki Masatoshi. 梵漢和対照. 現代語訳法華経(Lotus Sutra Sanskrit, Chinese, and Japanese comparison). Iwanami Shoten. Tokyo. pp.95-96

“/śāriputra tathāgatasyaika-krtyam eka-karaniyam mahā-krtyam mahā-karaniyam yena krtyena tathagato ‘rhan samyak-sambuddho loka utpadyate/ yad idam tathāgata-jñāna-darśna samādāpana-hetu-nimitam sattvānām tathāgato ‘rhan samyak-sambuddho loka utpadyate/ tathāgata-jñāna-darśna samdarśana-hetu-nimitam sattvānām tathāgato ‘rhan samyak-sambuddho loka utpadyate/ tathāgata-jñāna-darśnavatārana-hetu-nimitam sattvānām tathāgato ‘rhan samyak-sambuddho loka utpadyate/ tathāgata-jñāna-darśna pratibodhana-hetu-nimitam sattvānām tathāgato ‘rhan samyak-sambuddho loka utpadyate/ tathāgata-jñāna-darśna mārgāvatārana-hetu-nimitam sattvānām tathāgato ‘rhan samyak-sambuddho loka utpadyate/”

1/ Karmaloka (realm of desire), rūpaloka (realm of form), arūpaloka (realm of formlessness).